This year’s top articles from Faculty Focus is here.

My favorite in the list are Maryellen Weimer’s “Nine Ways to Improve Class Discussions” and Susan Spangler’s “Flipping Assessment.”

Adieus, 2015!

This year’s top articles from Faculty Focus is here.

My favorite in the list are Maryellen Weimer’s “Nine Ways to Improve Class Discussions” and Susan Spangler’s “Flipping Assessment.”

Adieus, 2015!

An article from Edutopia that talks of using humor to teach students mechanics of writing. The article gives examples of poorly written headlines that create faux pas or gaffes. It can get students’ attention right away about the grammatical and semantic aspect of the sentence. And when trying to fix the sentence students can learn hands-on the abstract concepts of grammar.

Stephen King makes a case that to produce more writing should not be dismissed as compromising on quality. And as always the man is worth listening to: “No one in his or her right mind would argue that quantity guarantees quality, but to suggest that quantity never produces quality strikes me as snobbish, inane and demonstrably untrue.”

“What sort of learner are you?” To start the semester with our students with this question is a useful exercise. It’s not surprising that many of us are not aware of our learning methods/strengths/styles. We think we know. Or we don’t think we need to know because it all seems so natural or reflexive. But such lack of meta-thinking won’t bail us out in case of unfamiliar learning circumstances. As Maryellen Weimer points out in the article, “In a workshop on using reflection to promote professional growth, I asked participants to spend some time thinking and writing about what they knew about themselves as learners. When we moved to a whole-group discussion, people talked about learning in general, not about themselves as learners. I didn’t have much luck getting the group to make it personal.” Though such an exercise on self-reflection in one’e learning style will be useful for any learner at any stage, I am particularly thinking of developmental writing or genre-based writing classes where students encounter a wholly new and complex writing challenge, and have to figure out the list of learning requirements that they may not essentially possess or be proficient in. Being aware of the required learning curve can build patience and help students with transfer of skills whenever applicable.

Last semester (Spring 2015), I did some serious reflection on my feedback to my FYC students. It was fueled by Nancy Sommers’ book Responding to Student Writers, which I came across in this article by Paul T. Corrigan. Sommers makes a compelling case for why feedback to students’ papers/writing needs to be succinct and pragmatic. Backed by Sommers’ own research and teaching experience, she argues that students get easily and frequently overwhelmed by lengthy and generic feedback by teachers. Teachers may think that they have a responsibility to point out every tiny mistake that the student makes, but such approach overloads students, leaves them discouraged, dents their confidence, and leave them with a less manageable plan to improve themselves as writers. Sommers advocates for a feedback strategy that takes an incremental or one-problem-at-a-time approach to motivate writers with a manageable and focused learning plan. Sommers also provides few useful templates on how to involve students in the feedback process. This recent article on Faculty Focus by Maryellen Weimer also echoes similar views for a “focused,” “concrete” and “descriptive” feedback to help students who are doing poorly in class. I implemented Sommers’ feedback method in Spring 2015 for two of my ENG 101 writing classes. It’s too early for me to claim any success. Also, I strongly feel that Sommers’ strategy may yield more beneficial outcome in developmental writing courses than in educational institutions where first-year writing students are already sufficiently developed writers.

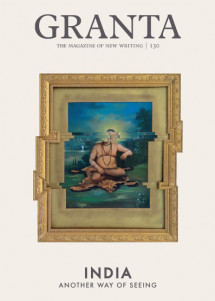

Granta’s issue 130, released in Winter 2015, is the second issue to have been exclusively dedicated to Indian writing in the journal’s history. In the year 1997, Granta experimented with first such issue. It was quite a hit, featuring writings by Anita Desai, R. K. Narayan, V. S. Naipaul, etc. This was the issue in which an excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things made its first public appearance. The issue 130 similarly features many known-names of the Indian literary scene.

Granta’s issue 130, released in Winter 2015, is the second issue to have been exclusively dedicated to Indian writing in the journal’s history. In the year 1997, Granta experimented with first such issue. It was quite a hit, featuring writings by Anita Desai, R. K. Narayan, V. S. Naipaul, etc. This was the issue in which an excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things made its first public appearance. The issue 130 similarly features many known-names of the Indian literary scene.

Most of the fictional pieces are glaringly open-ended. That could be because these works are excerpts from larger works, and perhaps a reason why they suffer from lack of compactness and impetus. On the other hand, the non-fictional essays, which clearly excites the editor Ian Jack as the promising new phase of the Indian literature, are meticulously researched, poignant, and evocative. My personal favorite is Samanth Subramanian’s “Breach Candy” for its incisive prying open of a discriminatory issue and punchy prose.

The litmag (literary magazine) scene in US is quite thick and overflowing. Being an Editorial Assistant and Blog Editor for the poetry magazine Spoon River Poetry Review, I am well apprised of the gruel and tenacity it takes to run a litmag. Yet, I am surprised by the enthusiasm and frequency with which new journals are conceived and run by writers and enthusiasts all around. From where does their optimism come? Don’t they realize how difficult it must be to invite quality writing when a writer has too many options? Don’t they realize how difficult it is to establish a brand name without money and manpower? The answer may lie in the accessibility and openness of the web age in starting an online journal. But in his review of Ian Morris and Joanne Diaz’s book The Little Magazine in Contemporary America, Stephen Burt disagrees:

A new journal needs a reason to exist: a gap that earlier journals failed to fill, a new form of pleasure, a new kind of writing, an alliance with a new or under-chronicled social movement, a constellation of authors for whom the future demand for work exceeds present supply, a program that will actually change some small part of some literary readers’ tastes. None of this has changed with the rise of the Web. Nor has the other big truth about little magazines which emerges from Diaz and Morris’s book, or from a day spent with anybody who runs one: it’s exhausting, albeit exciting, to do it yourself.

Summer can be tricky in setting productivity goals. Suddenly too much of time in hand. Overambitious writing projects. Mounting pile of books to read. I can already feel the adrenaline rush. I am determined as much as the last year, the year before, and the one before that that I will successfully check off the To-Do list by the end of summer. I won’t falter. By god, I won’t this time! But then I’m equally apprehensive that like the past this time too I will be left disappointed when summer will be gone and my productivity will look dismal on paper. This recent article on Vitae talks about setting realistic goals for oneself, and taking a very organized approach to the summer writing plan. This may sound cliché. And yes, that won’t be entirely false. But the goal is to accept that in summer (even without the teaching load) the time is limited, and to think that an entire year worth of writing can be caught up in just three months is going for overkill.

Also, another article by Joli Jensen that talks of maintaining writing productivity.

This post from Language Log felt personal for couple of reasons: first, It mentions my alma mater (NC State), and the highly important works done by the sociolinguists there on language diversity and educating people on non-standard Englishes and their validity; second, as a non-standard English speaker and writer, struggle with language is constant and draining. But then an article like this reminds me that this is not a losing battle.

As someone who has been mispronouncing “Colonel” until recently, this article on the word’s etymology is comforting. The word was originally spelled as “coronel.” Had that spelling been retained then the modern pronunciation would have made so much sense. Instead, at some point in the seventeenth century the word took a sinister turn: the “r” was replaced by “l.” And as is often the case with English language, the pronunciation failed to keep up with the spelling. Alas!